ESG and impact investment factors are of increasing concern to investors around the world. Assets in the sector rose 15% to US$52 billion during the first half of 2019 according to Fitch Ratings, showing how interest in ESG is experiencing rapid growth. According to the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN), the impact investing market is now worth US$520 billion. Sophie Chick, Head of Department at Savills World Research speaks to Lucy Auden, Global Head of ESG at Savills Investment Management to find out the reasons behind this sudden growth, and how it affects global real estate.

How would you define ESG and impact investment?

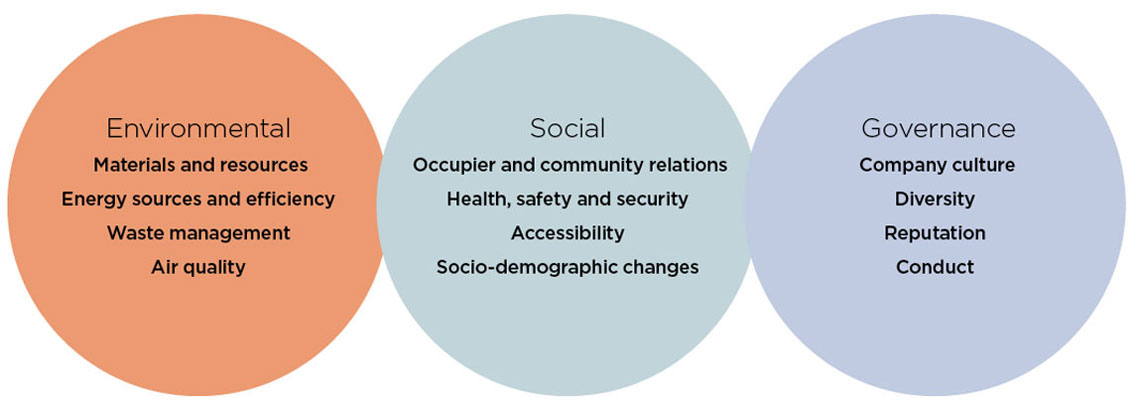

ESG is a toolbox that helps you apply environmental, social and governance aspects to your existing portfolio with the aim of enhancing its ESG performance. The E includes environmental aspects, such as climate change and energy sources. The S stands for social and includes factors such as the impact of assets on occupiers and communities, how new technologies are changing how we live, and socio-demographic changes such as ageing populations. The G is governance and includes things such as company culture, diversity, pay, reputation and conduct. While impact investing builds on these themes, the difference is intentionality: rather than enhancing the environmental, social and governance performance of existing portfolios, impact investing specifically looks to invest with the intention of creating a social or environmental impact, alongside a financial return.

Are there key characteristics to investments in impact investing portfolios?

I would say there are four. First, an investment needs to have the intention of creating a positive impact – an impact investment manager wouldn’t invest in a product that they didn’t think would have a positive impact – alongside a financial return. Second, ‘impact’ is embedded in the design of the fund, and that trickles down to the management process and will be part of the reporting metrics. Third, the performance of the impact is managed just as financial performance would be managed in the portfolio. Last, and this is where I think it’s a game changer, impact investing products aim to contribute to the collective growth of the impact investment industry. The intention is not to give individuals benefits over others, but for the collective action of multiple managers – for the whole industry – to create broader positive impact in relation to environmental and social needs. It’s different from traditional investing and philanthropy, it’s about the integration of impact into the investment process.

What are the trends contributing to its rise?

There is a wealth of factors. Social change is one – how assets have a real impact on real people. For us, in the real estate sector, we need to think more about what’s happening to the people using buildings as well as people in the communities surrounding those buildings. One of the places we’re seeing a social impact in real estate is affordable housing, social housing and supported housing.

The changing population demographic is also a contributing factor. A younger generation of pension-fund investors is asking how their money is being invested. They are looking at the environmental and social ranking of their portfolios, as well as financial rankings.

Also, there are many sustainability and socio-economic issues which will come from increasing urbanisation. The UN estimates 70% of the global population will live in urban spaces by 2050, many of those in informal settlements and slums. Issues surrounding this include housing density, urban agriculture and sustainable infrastructure – things which result from the interface of urban and rural contexts.

A broader awareness of environmental issues is certainly contributing, too. The UK government’s declaration of a climate emergency is a driver. In 2015, signatories to the Paris Agreement committed to try to limit global temperature increases to within a 2oC limit above pre-industrial levels. The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change’s (IPCC) 2018 report increased the urgency, stating this needs to be 1.5oC to avoid catastrophic consequences. With climate scientists predicting we are currently on track for a 3-4oC increase, there is a global movement of countries that are thinking about how to deliver on that goal. The UK government, for example, has committed to becoming net zero carbon by 2050, and within the UK there are a number of local authorities that are aiming for 2030. The collective action aspect of impact investment is essential for climate change – climate issues will only be solved by private sector, governmental, policy and community stakeholders working together.

Environmental issues and climate change are already driving real estate investment managers’ choices. Rather than saying, “I’m going to buy this green building as a ‘nice to have’,” the industry is starting to think: “If I buy an inefficient building and plan to do nothing to improve its resilience and efficiency, am I going to be able to sell it? With climate concerns on the rise, is there going to be a buyer in 15 to 20 years’ time who is willing to take on unmitigated climate-related risks?”

If you look globally at the number of cities that will be impacted by even a 1.5ºC temperature increase scenario there are quite a few in Europe. But, for cities in Asia and Africa the curve is exponentially huge. There’s a growing realisation that we need to be prepared for a new normal.

Does that mean ESG and impact investment is all about managing risk?

Absolutely! It’s interesting how it’s shifted from something that’s a ‘nice to have’ towards something that is risk led. As new environmental legislation comes in, a building could become a stranded asset risk. As climate change affects a region or city, could a building become a flood risk or not be able to cope with frequently increased temperatures in 30 years’ time? Many people are now modelling their assets’ climate-change resilience against a 1.5 or 2ºC increase in global temperature to assess stranded asset risk and direct portfolio management strategies.

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is essentially the financial industry’s response to climate change. Does real estate need a similar body? The bricks and mortar element of the real estate sector makes it much more at risk to physical climate changes. The built environment is also responsible for 40% of global carbon emissions, meaning there are also huge opportunities to reduce global emissions. The mitigation and adaptation of climate change both hinge on real estate assets in a massive way.

Are there certain tick boxes for specific funds to be officially classed as ESG?

Impact investing must meet goals to be classified as such, but the industry is grappling with uniform labels for what an ‘ESG fund’ needs to fulfil. At the moment, there are various bodies creating their own labels. For example, the Better Buildings Partnership has the Real Estate Environmental Benchmark (REEB). Then you have the Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark (GRESB), an ESG benchmark for real estate asset portfolios. For marketing purposes, GRESB-participating funds can publish that they contribute to the Benchmark to their portfolios’ carbon, waste, water, greenhouse-gas emissions, climate resilience, health and wellbeing, and governance aspects against others in their peer groups. But I do think investors are looking for simple ways of knowing whether they’re investing in buildings that are ESG-friendly, if they are going to be environmentally sustainable and make a positive social impact. The Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) benchmark measures indicators such as carbon intensity, social impact, data privacy and female board representation for wealth management portfolios. GRESB is the closest the real estate industry has to that, at the moment.

Is there a way of tracking whether ESG funds perform better than non-ESG funds?

Looking at more than 2,000 peer-reviewed academic studies on the correlation between sustainable investing and financial returns, more than 90% of these showed either a neutral or positive correlation between financial performance and sustainable investment (making sure they were accounting for previously considered environmental and social externalities). That’s pretty strong evidence that investing sustainably will not cause financial underperformance.

We think that this is happening in real estate, too. It shows through in values. The first way is looking at occupier costs. If you’re looking at any efficiencies, you will reduce cost in use. Will it reduce void rates as well? Occupiers are looking for new offices and they want to go to the most cost-effective ones. Environmental efficiencies go hand-in-hand with that. Tenants often say they’ve got a younger demographic of workers coming through and those people expect more of a co-working environment that has places to socialise, green walls, accessibility, plus health and wellbeing benefits. ESG can give you a broader pool of potential tenants, and help you avoid and reduce vacancies.

How do you measure the impact of ESG? Is there a way of demonstrating performance and track record to investors?

Environmental performance is easier to measure than social aspects, which require a more qualitative approach and can be highly context specific. You can say we’ve invested in this many social houses, housed this many people and provided economic support for this many people. But what is the socio-economic demographic of those people? Has the investment led to sustained, long-term social impact or just a one-off metric? Until you can answer that, you are not getting the full story. That’s why there are many frameworks being developed to try and measure social impact. The main priority is making sure that you’ve got both quantitative and qualitative measurements, because the financial industry is obliged to report metrics to shareholders and regulators. It’s particularly important for investors to understand these metrics because they are increasingly becoming required to report on fund performance to their own beneficiaries – and this includes the ESG performance.

How will ESG and impact investing develop during the next few years?

One of the challenges is scaling an impact investment while maintaining the integrity of the impact it set out intending to create. Measuring impact, including the nuances which come with qualitative social impact, can be costly. You need expertise, money and resource to accurately assess the performance, especially the social performance, of an asset.

Yet, all the factors I’ve mentioned, whether E, S or G, are only going to become more urgent in 10, 20 or 30-years’ time. The real estate industry is shifting – it’s realising that ESG issues will affect it and that we can’t wait and act in 10 years. We need to tackle the issue now.