The Ford Motor Company market their range of light commercial vehicles in the UK as the ‘Backbone of Britain.’ While a clever metaphor, that is where the analogy ends. In the automotive sector, and indeed, across much of the global economy, the true backbone is the semiconductor. This was a lesson learnt the hard way by Ford, as well as other major automotive manufacturers, after the chip shortage in 2021 forced them to shutter production.

In addition to being the key component powering everything from mobile phones to autonomous vehicles, the semiconductor best personifies how trends such as nearshoring and geopolitics are shaping the landscape of our globalised economy. Once dominated by the US (hence the name Silicon Valley), the semiconductor value chain has evolved into a globally interconnected system following the steady dismantling of trade barriers over the last three decades.

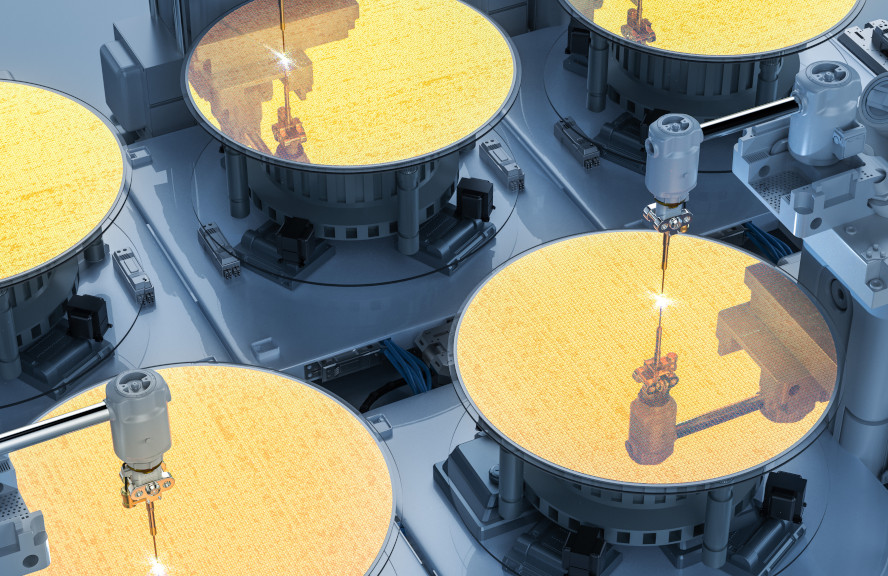

As globalisation was embraced, complexity at every stage of the value chain encouraged a high degree of specialisation. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) achieved great success by focusing on manufacturing, and now accounts for nearly 60% of global chip production. In the supply chain, two Japanese companies account for over 50% of the global market for silicon wafers, while ASML in the Netherlands is the sole supplier of the machinery required to manufacture the most advanced chips.

Semiconductor fabrication global market share by company and country

Source: Savills Research using Statista. Q4 2022 data.

Specialisation facilitated a rapid acceleration in technological progress, giving longevity to the observation from the 1970s by Gordon Moore – co-founder of Intel – that computing power double every two years (later to become ‘Moore’s Law’). But it also introduced an element of fragility in the value chain, which was exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Growing geopolitical tension further concentrated minds on where key economic inputs are sourced, especially those with a ‘dual-use’ purpose across both civil and military applications. Resilience in supply has now become an issue of national security.

With friends like these, who needs enemies

The result is a new enthusiasm for industrial policy. The US CHIPS and Science Act allocates over US$50 billion in incentives towards reshoring advanced semiconductor production. The European Chips Act is as close in name as it is in ambition and scale. China, Japan, and India are all pursuing similar strategies.

National security is quickly usurping cost as a principle driver of location. According to the founder of TSMC, US made chips will be more expensive than those produced in Asia. But this is not stopping them from ploughing a whopping US$40 billion into developing a fabrication plant (‘fab’) in Arizona.

There are concerns that government incentives will beget a global race to the bottom, while a ‘tit-for-tat’ trade war could bring the whole industry to its knees. The stakes are high, and when it comes to the technological frontier, every region has a trump card to play.

There is an effort to foster more cooperation. In 2022, the US and EU announced plans to develop “a transatlantic approach to semiconductor investment aimed at ensuring security of supply and avoiding subsidy races.” The US is also trying to foster a ‘Chip-4’ alliance to include South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan.

But China is a notable admission from these initiatives. And even allied nations are competitors in the global chip race. Not every nation can emerge victorious, and subsidising production and distorting the price signal risks developing overcapacity and wasting public resources. For their part, policymakers in Taiwan and South Korea are unwilling to give up their dominance without a fight; with the latter committing a staggering US$450 billion to the cause over the next decade.

When the chips are down, make Moore

Regardless of these concerns, legislation has been passed, and money is quickly being dispersed. The direct policy-fuelled investment is primarily focused on the development of new fabs. These are custom built, primarily owned and occupied by the likes of TSMC. Economies of scale are important. They need to be very large. And they are very expensive given the highly-specified processes involved. As such, it cannot be the sole domain of the industry to fund this expansion.

This provides an opportunity for other sources of private capital, and Brookfield Infrastructure Partners have already dipped their considerably sized toe in to the water by part financing a US$30 billion development of two fabs in the US with Intel, who described the deal as a ‘first of its kind’ for the industry.

The sheer scale of these fabs will restrict private sector involvement to the largest asset managers. But each fab will spur further investment in the local ecosystem. Other parts of the value chain are less capital intensive, less specialised, and so more accessible to private investors. Each will have its own real estate requirements.

Then there is the supply chain. Logistics is an obvious area that will see greater demand, according to Andrew Blennerhassett, European Logistics Analyst, Savills. “The intricate nature of semiconductor production necessitates substantial supply chain expansion, fuelling heightened logistics demand across all levels, from raw material suppliers to packaging and testing companies. These entities must either expand their industrial and logistics real estate or enlist third-party logistics companies (3PLs) to manage this growth.”

In Europe, we estimate that nearly 11.0 million sqm of logistics space is needed by 2030 to support the ambitions of the Chips Act. This is equivalent to 4.4% of total demand, based on historical rates of take-up. In the US, an additional 18.5 million sqm of real estate would be needed, which includes both office as well as logistics space.

The next question is where will this happen. While government incentives are distorting the market – particularly in the US where competition at the state-level further muddies the water – there remain other key drivers of location decision. In the words of Mark Russo, Senior Director and Head of Industrial Research in the US, “a multitude of factors drive site selection decisions for chip companies including workforce, utilities, local government incentives and even geological stability.” The availability of skilled labour, in particular, is critical to the construction and operation of new fabs.

Agglomeration economies are important. As highlighted by Russo, “similar to the EV gigafactory trend, the scale of these new facilities can be transformative for markets with supplier networks and additional knock-on effects creating new local demand for industrial property.” In the US, a majority of investment is concentrated in the Sunbelt, with leading global Tech Cities prominent, such as Austin and Dallas, both in the state of Texas. In Europe, the Saxony region (‘Silicon Saxony’) of Germany appears to be favoured. Shanghai and the wider Yangtze River Delta is home to the majority of Chinese fabs.

The concept of onshoring, nearshoring, friendshoring etc. is still primarily just that, a concept, evidenced mostly via extrapolating from the odd anecdote, or from citation counts of company earnings calls. But the semiconductor industry is at the coal face, and policymakers around the work are breaking their backs in an effort to turn concept into reality.