Along with the usual business mail and packages, a city-centre office can now expect a steady delivery of goods as employees take advantage of their workplace as a drop-off location for online shopping. What sets the office apart from home deliveries is the additional resource needed to deliver to a busy, congested environment far from a handy warehouse.

For cities everywhere, it’s just one example of how urban logistics is becoming more complex, putting pressure on the existing road network and demanding more space from urban real estate.

In his 2016 book The Geography of Transport Systems, Jean-Paul Rodrigue defines urban logistics as “the means over which freight distribution can take place in urban areas as well as the strategies that can improve its overall efficiency while mitigating congestion and environmental externalities”. Essentially, this means locating warehouse facilities close enough to their final delivery points while avoiding as much traffic congestion as possible.

So how big an issue is this for the real estate sector? With the rise of e-commerce fulfilment, the emergence of mega-regions and the continued focus on the environmental concerns of such activities, the real estate needs of tenants occupying urban warehouse space is expected to change in the future. Indeed, the EU’s 2011 transport White Paper established a goal stating the need for a zero-emissions strategy for urban logistics by 2030. Should this emerge into policy, it would suggest that more delivery facilities are required closer to population centres.

Delivering the right location

Whereas industrial real estate is focused around the production of commodities, urban logistics is about the distribution of those commodities – in particular the last leg of the journey to the consumer, wherever they may be at the time.

At present, these real estate facilities tend to be on the outskirts of cities. Although supply networks are in place, they were built to serve bricks-and-mortar high-street shops rather than the multitude of delivery destinations, such as customers’ homes and workplaces.

If we take London as an example and examine the variables that make it a beacon of interest in urban logistics, we can see a number of property and non-property factors working together to create disruption.

London’s logistical requirements

First, the property factors. London has an extremely low vacancy rate for warehouse property at just 2.5%. Indeed, the stock of warehouse property has been steadily declining as space has been lost to higher-value uses, such as residential.

In addition, rents for warehouse space within the city boundaries far exceed those further out. For example, all parts of London now record warehouse rents in excess of £11 per sq ft (£30 has recently been achieved for units smaller than 5,000 sq ft in the capital’s Zone 2 area).

Even at £11 per sq ft, this rent would still be about 50% higher than rent in areas located further away, such as beyond the M25 – London’s orbital motorway.

Non-property factors at play include a very high population density and, crucially, an extremely high daytime population. According to the London Datastore, there are approximately two million commuters and tourists in the city at any one time. This impacts supply chains, as workers have online deliveries sent to their offices, and the food supply chain caters for many more people than the population would suggest.

High need, low supply

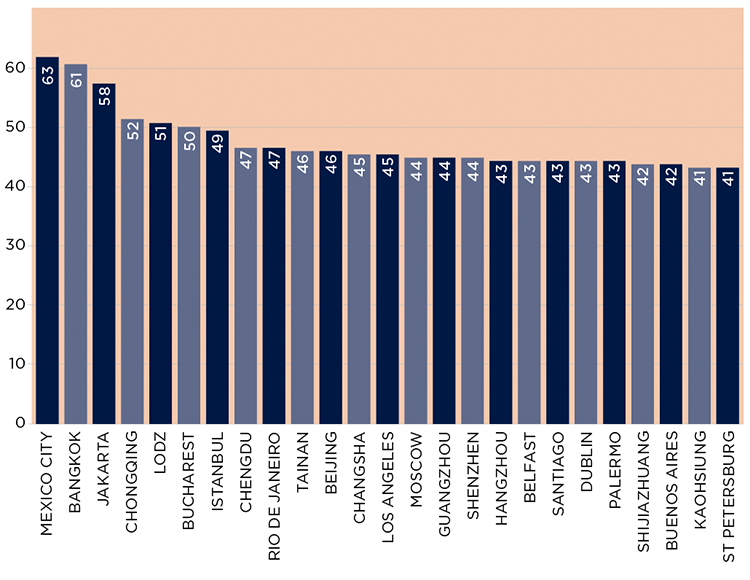

London also suffers from severe traffic congestion. During the day, it is almost impossible to travel across the city in less than one hour, meaning that warehouse units on one side of the city can really only serve that particular area. Congestion is even more severe in other cities, as the chart below shows – London doesn’t even rank in the top 25. This suggests that these cities will be high on the list to benefit from urban logistics innovation.

Top 25 Global Congested Cities. Increase in travel times compared with free-flowing traffic.

Source: TomTom Traffic Index Note: *Percentage increase in overall travel time compared with free-flowing traffic

Lastly, the UK has the highest online retail penetration rate in Europe with figures recently reaching 21.4% and rising. The additional deliveries associated with this form of retail mean that extra warehouse space is required in a market where the supply is already low. When the online retail rate hit 11% in the UK we saw a surge in demand for warehouse space. Currently, within Europe, only Germany has passed this 11% mark. Demand for urban logistics units in France and the Nordics is likely to surge as they are forecast to be next to pass the 11% threshold. These varied situations will lead companies to look at new ideas to service their requirements.

No individual factor is more important than any other in this equation, but in many markets around the world they are conspiring in different ways to disrupt traditional property markets and deliver innovative solutions.

The scale of urban supply

More than half of the world’s population now lives in urban areas, and the top 600 cities produce about 60% of the global GDP (Dobbs et al, 2011). Consider, too, that in the developed world, freight-intensive sectors of the economy (manufacturing, food) represent about half of commercial establishments, while employment and service-intensive sectors (finance, retail) represent the other half (Holguín-Veras et al, 2018). Both sectors need supplies brought in and shipments dispatched in varying quantities, speeds and timings.