According to the legendary investor Sir John Templeton, “The four most dangerous words in investing are ‘it’s different this time’.” However, the period post-global financial crisis (GFC) has been unique in terms of monetary policy, asset pricing and real estate investing.

The key characteristic of the post-GFC period has been how central banks have responded to its aftermath with a remarkably coordinated policy of quantitative easing and lowering of interest rates, to record lows in many domains. These policies were created to stimulate spending, and there can be no doubt that the world’s real estate markets have benefited. Real Capital Analytics estimates that the volume of capital invested in real estate (excluding domestic housing) rose from $600 billion in 2008 to $1.8 trillion in 2018. This makes it the most active year ever in the global real estate market, almost 30% higher than the last peak in 2007.

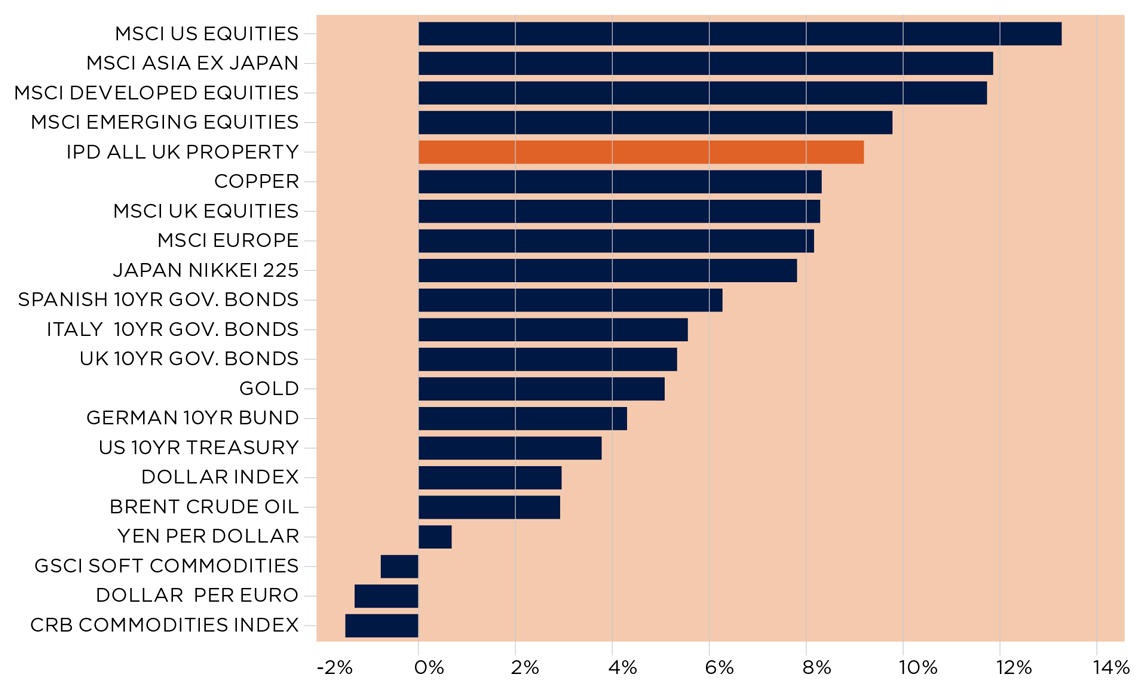

Low interest rates are not the only reason for the boom in interest in real estate as an asset class. Other drivers include financial liberalisation in parts of Asia-Pacific, as well as the rapid growth of some economies in the region. Erratic price movements in resource-producing countries have also played their part, as domestic investors seek to hedge volatility against stability. However, the key driver of the rise in attractiveness of real estate has been its comparatively strong return compared with other asset classes.

Traditionally, property has been positioned somewhere between equities and bonds in terms of investor characteristics and performance. This is certainly true over the long term. Since 1990, the average annual return from the three main asset classes is remarkably similar: UK 10-year government bonds showed 8.4% per annum, the FTSE 100 9.5% per annum and MSCI UK All Property 8.5% per annum. This feels like a rational place for real estate to sit – it is less liquid than equities and offers less security (but more upside) than bonds.

Real estate also has several other reasons to recommend it to the professional investor. These are well summed up in the Investment Property Forum’s regular publication Understanding UK Commercial Property Investments. This guide lists the pros and cons of commercial property as an investment (most of which are relevant to real estate across the world):

Pros

- Physical asset

- Relatively stable income return

- Capital growth potential

- Diversification benefits

- Risk/return profile

- Inflation protection

Cons

- Heterogeneous

- No trading exchange

- Large lot size

- Valuation, not market prices

- Transaction and management costs

Going back to Templeton’s concern, some of these factors clearly must have changed in the post-GFC period, but these changes probably have more to do with the weakness of other assets than any real difference in the attractiveness of property assets. As the Ten-Year Average Annual Total Return chart shows, property has crept up the comparative returns table, which has undoubtedly led to more money being targeted at the sector.

Ten-year average annual total return (GBP)

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

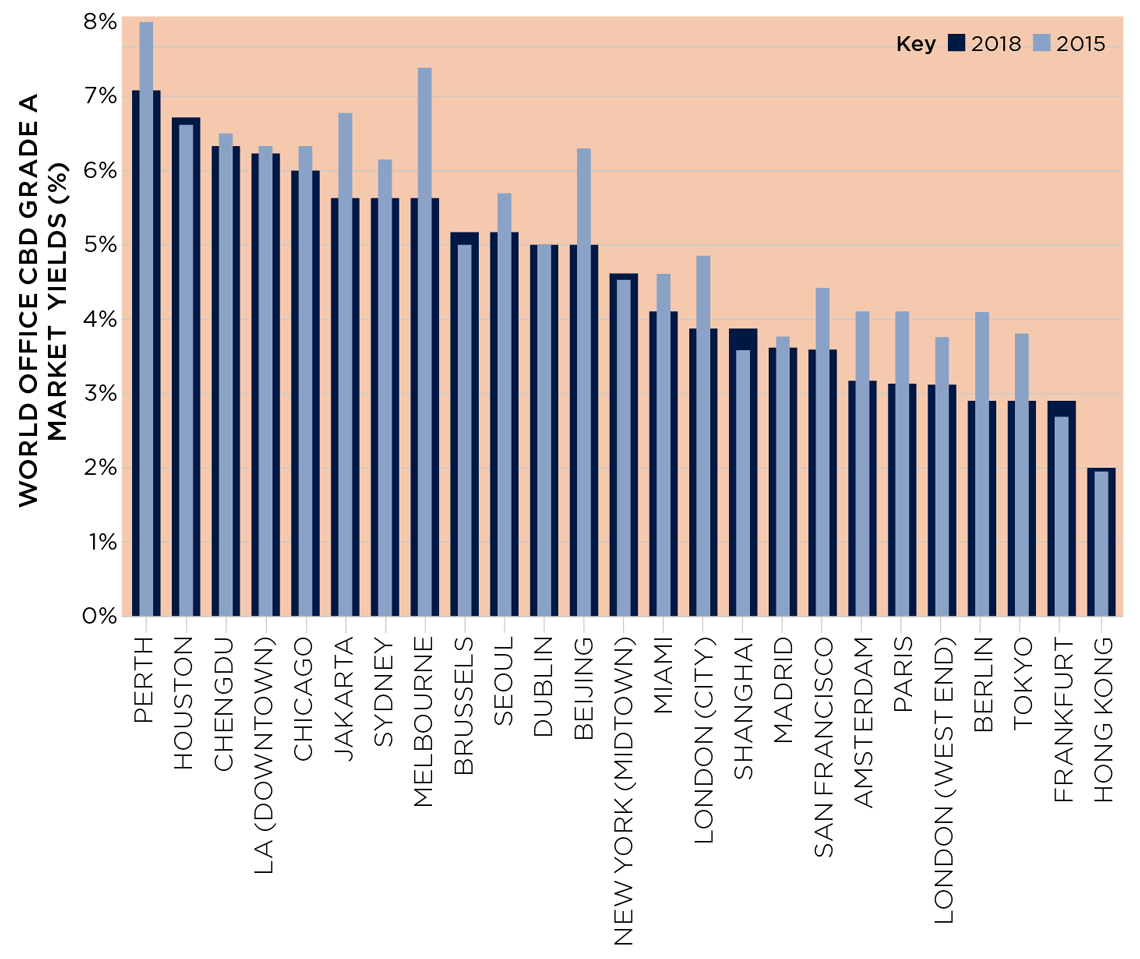

Greater investment in global real estate has led to a steady fall in yields over the last decade and, as the latest Savills World Office Yield Spectrum shows, prime yields in most markets are at, or close to, record lows in most of the world.

Yield Compression: Grade A Office Yields

Source: Savills Research

Increasing investor demand, rising prices and falling yields have affected far more than just the investment market for property. For example, they have made it less expensive for landlords to aggressively increase concession packages to avoid reducing their gross rents. Mitch Rudin, President at Savills in New York, points out that “these increased concession packages have enabled businesses to spend more on modernising their workspaces with the amenities necessary to attract the right talent”. You could argue that one of the most surprising impacts of quantitative easing has been the rise of the wellness and agile working agenda among employers.

However, the fact that most central bankers are talking about ‘normalisation’ of policy rates gives a clear indication that what was different about the past decade could change in the next. It is very unlikely that the rise in interest rates will be as synchronous as the fall. But with the US leading the pack, it is a safe bet that the future path for central bank rates, and hence sovereign bond yields, is upwards. Of course, rates are unlikely to go up in any one country until economic growth is strong, and strong growth usually leads to strong occupational demand for property – and hence rental growth.

So, what might normalisation of interest rates mean for property pricing? In my opinion, things may be a little different this time. A traditional fundamental pricing model for real estate yields is based around the assumption that the investor borrows money to fund that purchase. Thus, any movement in the risk-free rate of return should (and generally did) have a direct impact on the property yield.

However, a significant regulatory change has taken place since the GFC in terms of lenders’ attitudes to risk. Not only has the average loan-to-value on real estate lending fallen from 90%+ to 60%+, but the type of deal that lenders are prepared to lend on has also changed significantly. This, combined with a degree of risk aversion among borrowers, means that not only is there less speculative property development taking place around the world, but also that a far lower proportion of real estate investments are at risk of bank-led disposals if the market cycle turns down.

This means that, as and when base rates do start to rise in any domain, a similar rise in yields is by no means guaranteed. Indeed, the relationship has never been particularly strong unless rents have been falling during a period of rising base rates.

The relationship between base rates and property yields has also been further complicated by the type of investor that has been dominant in global real estate markets in the past few years. The rise of the global income-focused institution has increased the demand for stable returns. Many such investors now view property as more of an infrastructure play than a capital value-focused one. This has reduced the need to buy at the bottom and sell at the top, and led to a dramatic rise in interest in subsectors such as logistics and student housing that deliver a low but stable yield.

While the link between real estate yields and base rates has become less strong, it is by no means broken. Investors who look across a multitude of asset classes, and particularly those in search of longer-term secure income streams, will reach a point where the yield on sovereign bonds becomes attractive enough again to suggest a relocation of some money away from real estate and back into bonds.

So, as and when interest rates do start to normalise, the volume of money targeted at global real estate will reduce. This, in turn, will reduce downward pressure on yields on the most ‘dry’ and ‘core’ assets. Indeed, the mere fact they are rising might not be the most relevant factor as, according to Simon Hope, Global Head of Capital Markets at Savills, “any perceived risk around rising interest rates does not lie in the rise itself, but rather the rate at which the rise occurs”.

However, I do not expect real estate yields to move in lockstep with base rate rises, as the global appetite for income-producing assets will remain strong. This then creates opportunities for those investors whose business model has always been about creating the product that more risk-averse investors want to buy. Arguably, the rising prices and falling yields of the past decade have made it harder for value-add and opportunistic investors to source development and asset management opportunities, and modest rises in yields should make this easier in the years to come.

So, are things going to be different this time? Well, yes. But only slightly. And the difference is more about returning to pre-GFC normality. Once again, the best opportunistic investment strategy will be the traditional one of buying short income and turning it into long. As ever, out-performance will come from local market knowledge, an understanding of the structural changes affecting occupational demand, and an ability to look behind the headlines and focus on fundamentals.