“Municipal extravagance, excessive outlays on magnificent buildings, at high cost, on borrowed money… overexpanded subdivision activity, and a disproportionately large amount of real- estate purchases on small down payments.”

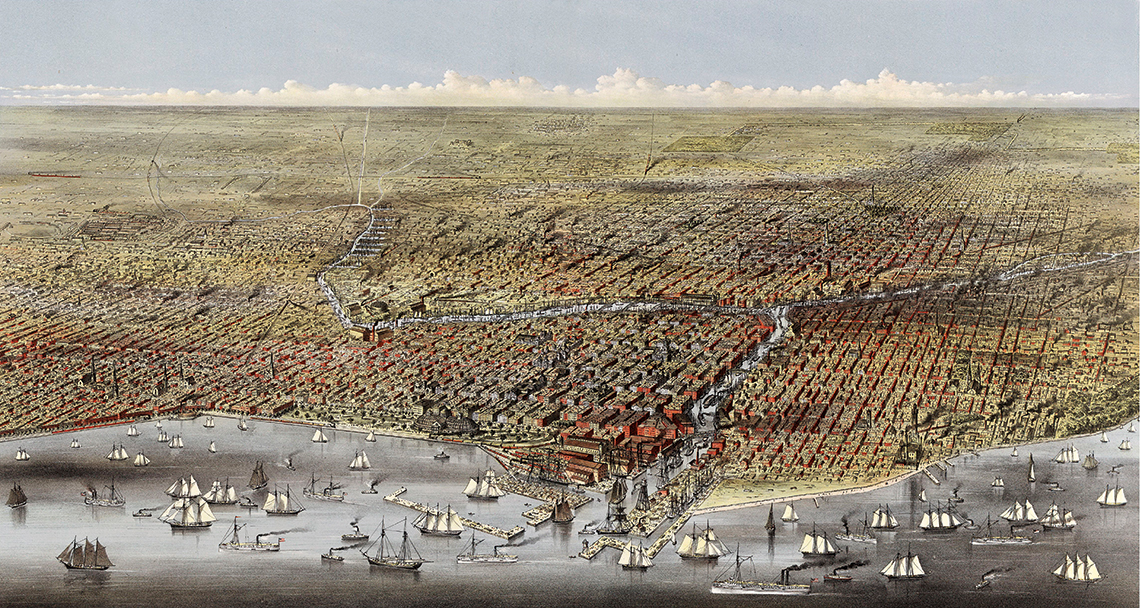

This reads like a play-by-play of the global financial crisis (GFC) that started in 2007, but it’s actually how US land economist Homer Hoyt depicts the collapse of Chicago’s real-estate market during the Panic of 1873 in One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago.

The first two centuries of American history provide no shortage of development schemes that failed several times, but eventually succeeded, partially due to timing, but largely because of private investors or banks willing to restore value to what seemed to be lost causes.

Chicago’s first land rally began in the mid 1830s – investors rushed to acquire land along the Chicago River as excitement about canal and rail development soared. The timing was unfortunate. A banking crisis unfolded in 1837 and banks in New York City and Europe pulled their horns in.

Subsequent rallies and busts in Chicago followed a similar pattern of assumptions taken too far or overly risky choices, including one in the late 1850s, when investments in bonds held by Southern States achieved higher yield requirements, but set the market up for a fall once the Civil War began.

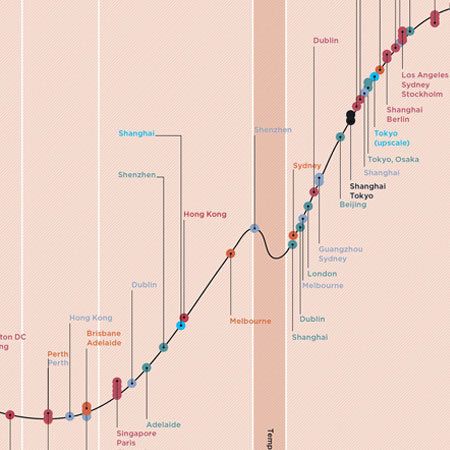

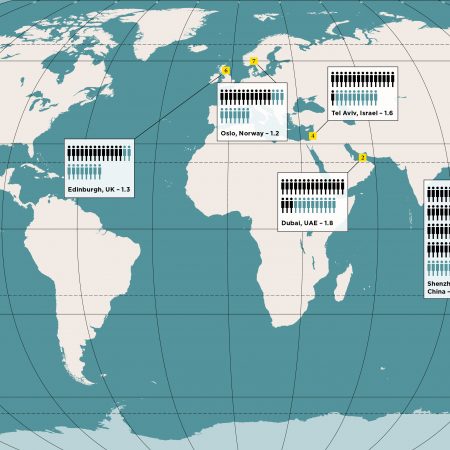

The magnitude of real-estate bubbles varies widely. They can be brief, localised episodes or, as in 2008, they can be the basis for extensive market collapses. In his book, Hoyt repeatedly highlights the pressure of easy money and a surplus of funds for investment as a trigger for particularly massive fallouts.

Risk taking is inherent in the pursuit of yield, making the containment of markets a constant battle. But savvy investors bank on at least one rule holding true – by definition, peaks are followed by troughs, and vice versa. In order for a real-estate bubble to blow up to the scale of the Panic of 1873 or the GFC, the market must experience the reversal of key assumptions and expectations that have widespread acceptance. In retrospect, suggesting that railroad bonds can’t fail, housing values can’t fall or that a tech rally is different, seems like madness.

Image: Shutterstock