Our experts

Andrew Baum Visiting Professor of Management Practice, Said Business School, University of Oxford (above left)

Linda Yueh Fellow in Economics at Oxford University and Adjunct Professor of Economics at the London Business School (above centre)

Akhil Patel Director of Ascendant Strategy and editor of Cycles, Trends and Forecasts investment newsletter (above right)

Impacts It is argued that property cycles in the UK and the US have historically been seen to run in 18-year cycles. But are they now a thing of the past?

LY Business cycles are not really ‘as usual’ at the present time, due to the unusual systemic financial crisis that the US and UK recently experienced. Instead of a short and sharp recession and recovery, the current business cycle is characterised by weak growth and credit constraints, which will affect the property cycle.

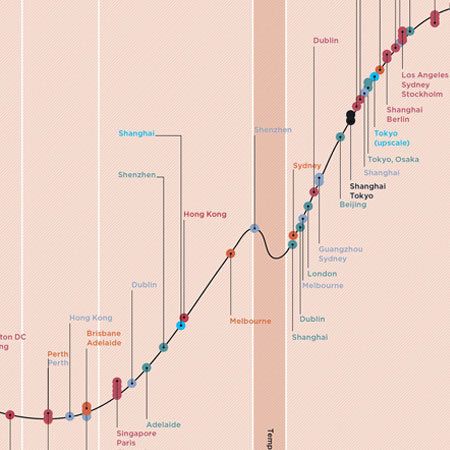

AP If you know your history, you’ll see evidence of the 18-year cycle in the UK and US going back over 200 years. My research suggests more markets across the globe are following the same cycle. This started with reconstruction after World War Two, which ‘reset’ many markets at the same time. The global financial crisis (GFC) similarly affected many markets simultaneously.

AB We have no strong evidence for 18-year property cycles. There have only really been three big crashes in history that we would regard as reliable evidence – and the two gaps just happened to be 18 years apart. There’s a danger that we could be extrapolating too much from something that could be pure accident. Waves in the availability of finance, particularly debt finance, could be more interesting to look at. If there’s debt availability, you get more building, which sets up a boom in rents.

How much do the UK and US cycles affect the property markets in Asia and Africa?

AP The cycle seems to occur in any place that follows a Western-style model with private property rights and bank lending. As other countries have joined the global economic system, we can see the same patterns of boom and bust. But because the historical evidence is not as comprehensive as the US or UK, this leaves us questioning: are they experiencing the same 18 to 20-year regularity that we see in the West, and are they following the same timing? The answers will emerge in the next five to 10 years.

AB It’s a difficult question. Global capital flows are somewhat driven by the returns available in other global markets. If the UK has a price boom, then there is more likely to be money from China to go into it. The UK is slowing down now, but a cheaper pound, plus a desire to get money out of Hong Kong driven by Chinese politics, is supporting the top end of the UK market. Over-pricing in the core markets will help push more money to developing markets eventually.

LY The US cycles affect Asia more than Africa, since the former is closely linked by trade and exchange rates to the US. Asia and Africa are at different stages of economic development: in Asia, the property markets will reflect the fast-growing middle class; and in Africa, they are still industrialising and therefore slightly slower-growing nations.

What factors are significantly altering our understanding and forecasting of property cycles (Brexit, for example)?

AP I think the impact of the Brexit vote on the property cycle on both sides of the debate has been overstated. Events such as Brexit or, in the 1990s, the UK crashing out of the exchange-rate mechanism, tend to fit in to the broader pattern of the economic cycle. The frustrations behind the vote were clearly a consequence of the GFC, which is part of the cycle.

AB We’re going through a period in the UK of very low bond yields and interest rates, so the property market is awash with cash, but there is a shortage of high-quality investments with reasonable returns. However, our expectation about rising interest rates keeps getting pushed back – most people have been incorrectly forecasting rising interest rates for at least eight years. The fact is we do not know. For example, you would expect there to be a building boom now in London, but Brexit has taken the developers’ confidence away.

LY The economic factors to watch are investment and consumption. If Brexit or the Trump administration’s policies increase uncertainty, then that could have a dampening effect on investment. Consumption trends are also important as a driver of economic growth, which in turn supports the residential and commercial property markets.

Should investors just not worry about property cycles altogether?

AB Probably not. The importance is overrated. Markets move at different speeds. You have to look for the scientific evidence and a supporting theory. The hog cycle might help to explain office development, but do we really believe we are in a price cycle when we don’t understand how QE works?

AP The 18-year property cycle is a historically robust macro-framework. It’s both explanatory and predictive; it ties together what’s going on in property and credit markets; it helps with market timing and affects decisions on finance. You simply can’t ignore it because the most risky decisions tend to be when everyone is the most bullish about the future, which, in the cycle, is at the peak – around 14 years after it starts, and is soon followed by a four-year depression and recovery period.

LY I think investors should pay heed to the business cycle and the impact the overall economic environment has on their specific sector. But, the global economy and a number of major markets are undergoing huge structural changes, so it is a far trickier business to understand economic cycles in the 21st century.