US cities may occupy the higher reaches of the Savills Tech Cities Index, but Chinese cities are rising fast, claiming a higher share of global venture capital investment in the process. Kevin Kelly, Senior Managing Director, Savills in the US, and James Macdonald, Senior Director, Savills Research, China, discuss the key attributes, technologies and influential companies that shape a tech city in their respective markets, plus the implications for real estate.

Is there a key attribute that defines a tech city – setting it apart in terms of innovation and investment?

Kevin Kelly: Each tech city has its own story, but a common thread is the presence of great universities in the area. In California, Stanford and Berkeley have driven innovation and the growth of companies in San Francisco and San Jose.

However, when you combine these factors with quality of life, there are different drivers for different cities. For example, fewer people in their early 20s are moving to San Jose – they prefer San Francisco. This demonstrates that a city’s ability to attract talent varies – quality of life and urban layout are big factors.

James Macdonald: Beijing has the best universities in China, and these are a source of talent for tech firms as well as being incubators for new ventures. Hangzhou is the home of Alibaba and this has driven the tech economy in this city. It is also one of China’s most liveable cities. Shenzhen constantly reinvents itself, from a centre of manufacturing to hardware and now to software and finance. It also has a dynamic and ambitious population of immigrants from all over China.

Simon Smith, who’s based in Hong Kong and Head of Research for Savills Asia-Pacific, believes Hong Kong is becoming a fintech incubator because it is a global financial centre and the first staging post for Chinese financial services companies who want to expand internationally.

KK: Even though it is one of the most expensive cities in the world, young people want to be in New York for its overall liveability as well as its tech reputation. Young, educated people, especially in tech, worry less about affordability for housing and other costs when moving to a tech city. For those starting a family, it’s more complex. Even in lower-cost places, such as Austin, Texas, it’s difficult to find suitable residential property downtown.

Which cities have developed tech specialisms and what are the implications for real estate?

KK: In the US, the hotbeds for hardware are in Austin and Boston, biotech in Boston and San Diego, and music- and film-related tech in Los Angeles. This is often the result of a feedback loop with local universities. Clusters of businesses emerge from the computer science output of a particular college. That local specialism then feeds back into the curriculum. St Louis, Missouri, which is outside the top six in the US, has become a centre of expertise for security-related tech, while fintech is thriving in Atlanta thanks to Georgia Tech.

As companies cluster in micro-areas, the main real estate issue is rising rents. In New York, rents have exploded in Midtown South, an established tech location, and are now on par with traditional Midtown space. In San Francisco, space downtown is leasing at such a rate that if you are looking for a large block, you have to get in early and bid for it. Companies have to take into account what is most appealing not only for their existing employees, but where talent will want to live and work over the course of the lease. Take Austin, for example. Companies here would rather face the traffic to work downtown, where rents are $50-60 per sq ft, rather than locations that are $20 per sq ft but 15 minutes’ drive away.=

JM: The Alibaba effect has made Hangzhou a hub for consumer-focused tech, thanks to the presence of the online shopping giant and companies who hope that being close to one of China’s unicorns will boost them. Chengdu, in western China, offers cheaper labour than the eastern cities, so has become a low-cost, high-tech centre and a centre for business processing outsourcing, a big driver of the office market. Media and content are heavily regulated in China, so tech firms in this sector need to be close to the administration in Beijing. Shenzhen is home to a myriad of app developers and these smaller companies are often looking for flexible workspace.

These cities are top of the list for global tech companies. What factors drive their location decisions?

JM: International tech companies choose China because of its market size and because the Chinese are willing to try new technology. That’s why China leads the world in online and mobile shopping. A key factor for rapidly growing tech companies is the attraction and retention of talent. This means university cities, such as Chengdu, Beijing and Hangzhou, are favoured locations. Shanghai is the financial capital and the most international mainland city, so it is a prime location for a company to locate its headquarters.

Simon Smith adds: “Hong Kong is Asia’s most dynamic and well-rounded city, with a diverse international talent pool. It is a place people want to live and work in.”

KK: Despite the immense power of the big tech brands, such as Amazon and Apple, recruitment for talent is still highly competitive. Amazon initially picked New York and Washington DC as its new secondary headquarters, before later pulling out of the New York deal. It could have differentiated itself with a new and unique location, but instead chose two of the largest, most expensive cities on its list. Ultimately, scale was the most important factor. I think those New York jobs will now be incorporated into an expansion at a planned site in Nashville, Tennessee.

What is interesting about the Amazon decision is that, for other large tech firms, location choice is also driven by the need for employees to find housing. Traditional tech cities are all expensive, making places such as San Francisco difficult to raise a family and have a reasonable commute. For most metro areas, housing gets cheaper as you move out from the urban centre. But in the Bay area, costs remain extremely high even as you head out of the city.

How have the real estate markets of these cities responded as tech companies have become major occupiers?

JM: China does not wait for business to make decisions about location; the government sets out areas where it wants to see certain kinds of businesses and development. Shanghai has been declared an AI [artificial intelligence] hub, so there will be zoning and incentives to ensure AI companies make it their home. Along the road between Shanghai and Hangzhou, a series of towns have been allocated specialisms to form a tech corridor.

KK: Clustering is the most obvious way cities are being shaped, as tech companies grow to be major occupiers. This is happening much more within cities such as New York and San Francisco. It used to be that the fastest-growth tech was in the boroughs and outside classic urban residential areas. Now, in Boston, New York and Austin, this clustering is happening

in proper downtown environments.

A second major trend is the expansion of co-working space, which has gone hand in hand with the growth of these tech cities. Co-working companies, such as WeWork, are themselves dominant occupiers, providing repurposed office space for young start-ups and incubators.

Tech cities are leaders in shared mobility services and pioneers in clean transportation. How have they responded to the challenges and opportunities posed?

JM: China is the birthplace of bike sharing, with companies such as Mobike and Ofo leading the market. Ofo has more than 20 million users, mainly in larger cities such as Shanghai and Beijing. China’s ride-sharing app market is also incredibly competitive, with a number of new apps competing with market leader Didi Chuxing, which bought Uber’s China operation.

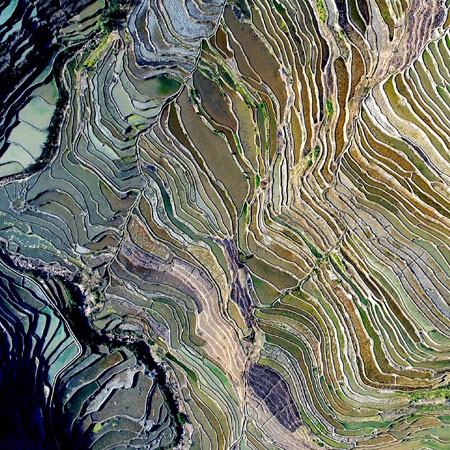

China is also leading the world in public transport development, with plans to invest $300 billion in metro systems between 2010 and 2020. At 676km, Shanghai has the longest metro system in the world, and there is 120km of track under construction. The growth of public transport has been crucial for real estate development, which is often centred on transport nodes.

KK: Shared mobility aligns with the innovation in tech cities, so they have become natural testbeds. However, they are finding it difficult to make it resonate with the existing transport infrastructure. This is partly down to human psychology: unless there is a cost or time saving for shared cars or bikes, it is difficult to take more time to do the right thing. We also see city planners struggling with oversupply, so this is going to continue to be a city-level debate with different answers in campus versus metropolitan cities.

Where are the tech cities of the future?

JM: Guangzhou is the only first-tier Chinese city not in the Tech Cities Index and it has plans to become a centre for cross-border e-commerce. A new central business district and e-commerce hub is planned for the Pazhou district. The government also wants to develop regional centres. Xi’an in northern China is expected to benefit from this. The university cities of Wuhan and Nanjing are also contenders.

KK: Raleigh, in North Carolina, is a rising star. It has great universities with computer science programmes – University of Carolina, Duke University – as well as a cluster of biotech companies. It is experiencing an explosion in hardware and software talent. IBM bought Raleigh-based software provider Red Hat for $34 billion –the world’s second-largest tech deal.

A more unusual pick is Nashville. We looked at the ingredients that made Austin successful in the early days, such as scale of output, residential costs and nightlife, and then ran those metrics for cities today. Nashville came out on top.