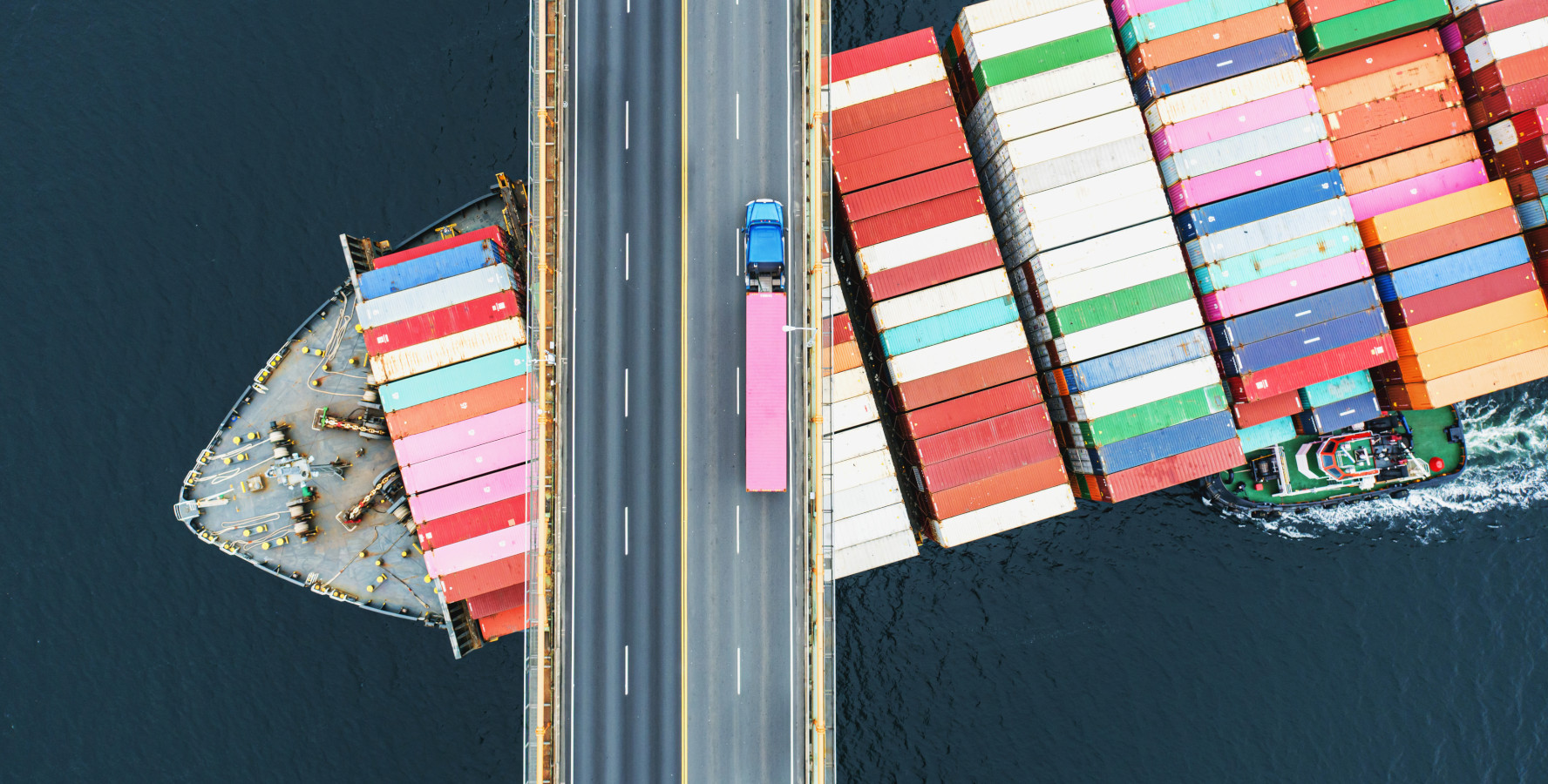

Against a backdrop of transportation bottlenecks, geopolitical tensions and ambitious sustainability targets, the logistical shocks from Covid-19 made businesses rethink their global supply chains.

Nearshoring emerged as one of the solutions – the Savills and Tritax EuroBox 2023 European Real Estate Logistics Census found that occupiers highlighted a “reduction in reliance on foreign imports” and a “shortening of supply chains” as the top two changes planned for the next two years.

As occupiers look at new location options across different geographies, they are faced with difficult decisions. Location selection is a multifaceted choice; ideally, there would be a warehouse with low operating costs, in a market with high ESG standards, stable geopolitical relations, an open and transparent business environment and geographically close to key consumer markets.

In the real world, however, this ideal warehouse doesn’t exist – so occupiers have to make a decision based on what’s most important to them. Our 2022 Nearshoring Index ranked 54 locations based on four pillars that influence this decision: resilience, economic cost, business environment and ESG. The 2024 update analyses a subset of key manufacturing locations with an expanded view of the economic cost pillar to include rents and energy costs, in addition to labour costs.

Amid global integration and falling trade barriers, companies originally chose to offshore production as a cost-saving measure. But when supply shocks hit and companies became more concerned with their ESG performance, many looked to nearshoring as a potential solution.

Reorienting global supply chains is not cheap and with inflation and interest rates hitting multi-decade peaks over the past few years, the issue of cost is once again at the forefront of the discussion. Rising rents are occupiers’ main concern, according to the European Real Estate Logistics Census.

But herein lies the dilemma – locations that score well in our economic cost pillar don’t tend to score as highly in our resilience, business environment and ESG pillars.

Markets that are resilient, have good business environments, and ESG credentials tend to be more expensive

Source: Savills Research

Low cost hubs remain popular

Low cost hubs have traditionally been the largest beneficiaries of offshoring, and this doesn’t appear to be changing as occupiers continue to be cost-conscious. Vietnam and Mexico, for example, have performed better on our Nearshoring Index this year as their cost differential to other markets has increased with the inclusion of rents and energy costs. These lower cost locations are also experiencing increased demand from manufacturers; Vietnam, for example, is home to Intel’s largest global factory, and Samsung now builds half its phones there.

Many companies, such as Volvo and BYD, have looked to manufacture in Mexico as a cheap gateway to American consumers. This has happened at such a scale that by the end of 2022, Mexico overtook China as the US’s largest source of imports – a standing it has maintained.

Nearshoring, however, is not onshoring – meaning there may still be issues regarding borders. A number of occupiers in Mexico have struggled with importing goods into the US. In order to reduce the impact that border delays have on the supply chain, occupiers aim to stockpile goods in border towns and then transport them across the US. This has led to an increase in take-up in cities such as El Paso.

‘China plus one’ strategy

While these lower cost locations have seen increased demand from occupiers, the complexities and expense of unwinding existing supply chains cannot be ignored. Western companies aiming to diversify away from China due to increased Sino-US geopolitical tensions are having to deal with the fact that the country remains the world’s largest exporter. Because of this, as well as China’s high-quality infrastructure and large labour force, many companies have had to adopt a “China plus one” strategy – largely benefitting Thailand, Vietnam and Mexico.

As the world’s second largest economy, China is incredibly embedded in global supply chains. Although Mexico has overtaken China as the largest US importer, Chinese imports to Mexico have increased by 91% over the past five years, according to the China General Administration of Customs. Americans may be buying an increasing number of goods from Mexico, but these imports still rely on components made in China.

For businesses targeting European consumers, locations such as Poland, Portugal and the Czech Republic often provide a rare “Goldilocks” solution – they are low cost, but are part of the European single market, which offers open borders, free movement of capital and stability. As such they continue to perform well on our index and take the top three spots.

In APAC, South Korea appears to be offering a similar solution. The country offers a highly educated population, an open and transparent business environment and has relatively cheap operating costs.

Higher-value production in high-cost locations

Expanding the economic pillar to include all operating costs means some advanced economies have fallen down the rankings. However, there are examples of manufacturers choosing these locations, often to access higher-skilled and higher-valued production. This tends to be in sectors that are more sensitive to geopolitics, as well as trade and industrial policy, such as semiconductors, electric vehicles (EVs) and energy.

Sweden, for example, is becoming a hotspot for battery investment from both domestic and foreign manufacturers, such as Northvolt and Shanghai Putailai New Energy Technology. Over in the UK, take-up from manufacturers has seen more growth than any other sector, rising by 32% since 2021, and now accounts for 58.5m sq ft of UK warehouse space.

This trend is most evident in the US, which has seen an upshoot in manufacturing jobs – since the Covid-19 pandemic, over 870,000 manufacturing jobs have been announced, according to the Reshoring Initiative. This is double the number announced in 2017-19. However, it is worth noting that 39% of announced manufacturing jobs last year were in EV batteries, semiconductor chips and solar energy – all sectors supported by the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), CHIPS and Science Act and other government subsidies.

When nearshoring began to emerge as a post-Covid-19 megatrend, there were concerns about a global supply chain upheaval. What has occurred so far is more of a subtle change. The current manufacturing trends appear to show that although companies are setting up in new locations, they are still prioritising reducing costs and increasing economic efficiency – which was what drove global supply chain offshoring throughout the 1990s and 2000s. While this helped to create the post Covid-19 supply shock chaos, increased diversification of supply chains via nearshoring can help buffer shocks and, in turn, reduce the volatility felt by households.

Nearshoring Index 2024

Source: Savills Research

Nearshoring Index 2024 Methodology

To illustrate the potential shift in global supply chains, we developed the Savills Nearshoring Index. It captures the factors that influence the decision of companies on where to locate activities. It is composed of four pillars:

- Resilience characterised by domestic stability and proximity to local markets.

- Economics driven by the cost of labour, energy, and warehouse rents.

- Business environment underpinned by ease of doing business, quality of infrastructure, and absence of trade barriers.

- ESG underpinned by environmental and labour standards.