It’s the first day of summer 2024 in the US and 100 million Americans find themselves under heat advisories. A high-pressure system known as a heat dome brings prolonged temperatures above 32°C (90°F). The Midwest and East Coast bear the brunt of it – Washington DC swelters in 38°C (100°F), some 12°C (22°F) above the seasonal average.

Last year was the world’s hottest on record, and exacerbated by climate change, extreme heat events such as this are becoming more common. Global temperatures reached another record average high in June this year – the 13th record monthly peak in a row.

Difference in temperature to 20th Century average, global land and ocean

Source: Savills Research using National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Difference in temperature to 20th century average, by country in 2023 (degrees C)

Source: Savills Research using National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Cities are particularly at risk of extreme heat. The urban heat island effect means that they can be 5°C (9°F) to 10°C (18°F) warmer than surrounding areas.

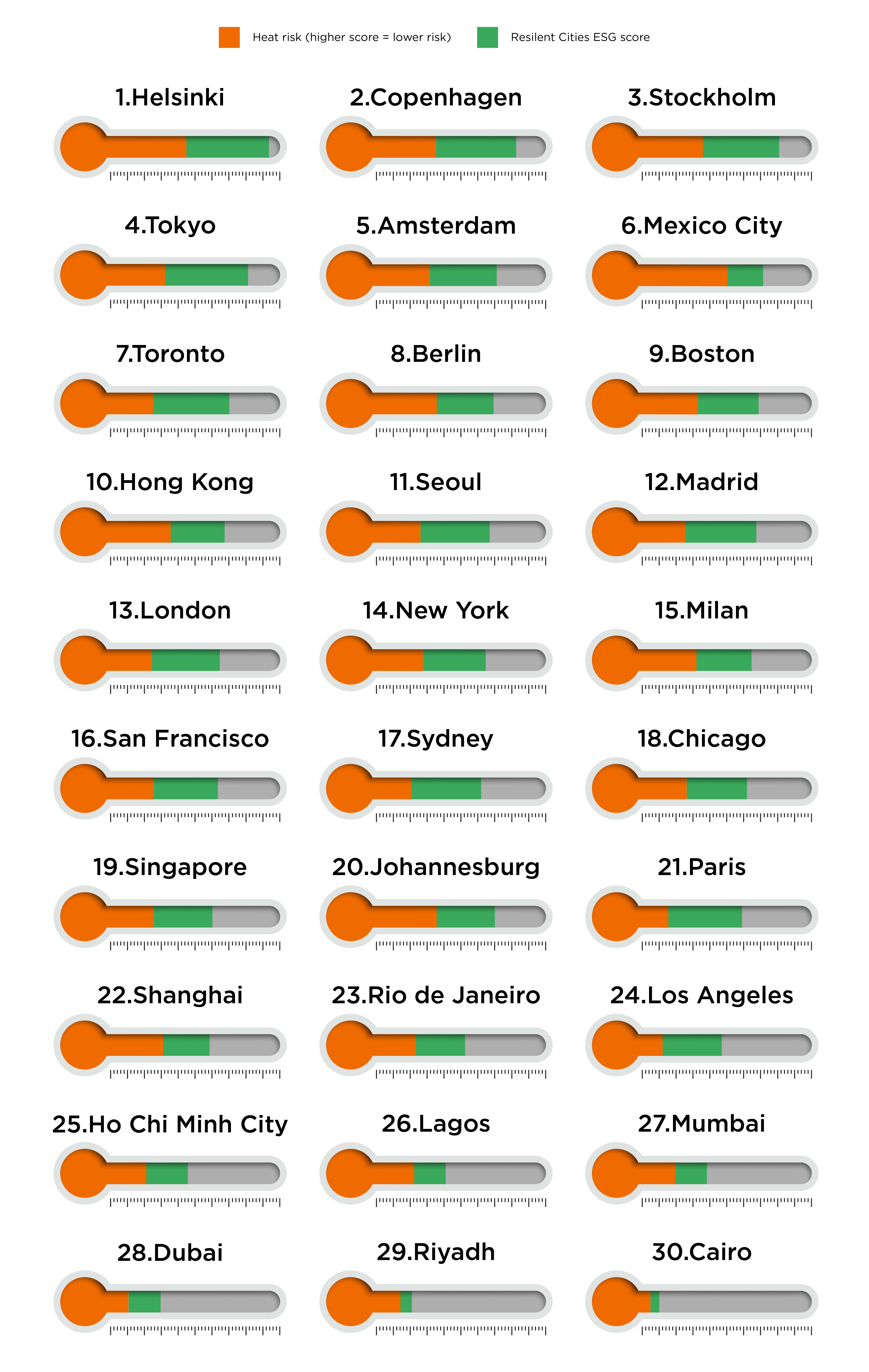

The Savills City Heat Resilience Index assesses 30 global cities based on their risk of extreme heat and resilience to it. A trio of Nordic cities lead the way: Helsinki, Copenhagen and Stockholm. Here, extreme temperatures and days over 30°C (86°F) are rare, while progressive ESG policies help to mitigate the effects of extreme weather on their populations.

But even top-ranking cities face risk. Heatwaves are especially dangerous in places where buildings are not designed for extreme temperatures. Conversely, cities that regularly experience days over 30°C (86°F) may be more adapted to hot weather, through extensive use of air conditioning. But access to this and other heat-mitigation measures could be limited by social inequality.

Measuring urban heat resilience

How does the index work?

Our City Heat Resilience Index takes into account a city’s record temperature high, the difference between that and the average summer high, and the number of 30°C (86°F) days experienced in 2023. It sets that against the city’s Resilient Cities Index ESG score, which tracks a city’s environmental practices, social policy and governance. Higher-scoring cities should be better prepared to deal with the physical risks of extreme heat and its impact on their inhabitants.

Heat resilience index

Source: Savills Research

Difference between record temperatures and average summer high

Temperatures more than 15°C (27°F) above the seasonal average have been recorded in 60% of the 30 cities we analysed, while half endured more than 50 days above 30°C (86°F) in 2023.

Source: Savills Research

Cities and buildings must adapt to the new norm. Natural canopies, reflective building materials, green roofs, and passive cooling can reduce building heat and lessen demand for air conditioning. This is important; in extreme heat, air conditioning units have to work harder, so they emit more heat and greenhouse gases, compounding urban heat accumulation.

Excessively hot nights limit the body’s natural cooling process; they also tend to generate higher temperatures earlier in the day that persist longer. This results in heat stress that can exacerbate underlying illnesses – a factor that contributed to the 70,000 excess deaths recorded during the European heatwave of 2022 alone. Older people are more vulnerable, whereas those of lower socio-economic status – living in a home without air-conditioning or having no home at all – are more exposed to the risks.

These social implications must be understood by the real estate industry and policy planners, says Chris Cummings, Director, Savills Earth: “Urban heat should be considered by authorities when planning large regeneration schemes – especially where they involve densifying, as this can intensify urban heat, and it is existing local communities that may be impacted most.”

Owners of real estate assets and portfolios face two types of risk from heat. There’s transitional risk – ensuring assets can be adapted to meet a changing climate efficiently, so that energy use aligns with future legislation. Then there’s physical risk – excessive heat can physically damage building materials, so a higher level of structural resilience is required. Ignoring either may lead to reduced values and, at worst, stranded assets.

Mitigating measures for urban heat extremes

Buildings can’t be considered in isolation. The spaces between buildings are especially important in tackling urban heat. Organic streetscapes have a natural advantage here, as their mixture of road alignments draws wind flow more effectively than urban grids can, enhancing their natural cooling properties.

Los Angeles is also making use of its streets – by painting them with a heat-reflecting grey coating that’s shown to reduce the surface temperature by up to 9°C (16°F). This complements the Los Angeles Green Building Code’s ‘cool roof’ requirement that residential roofs meet minimum values for solar reflectance.

And in 2005 Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon stream, which used to be hidden under a four-lane motorway, was restored. It has since cooled its surroundings by up to 5.9°C (11°F).

However the economics of real estate mean the potential benefits of green or blue spaces are not always maximised. “Higher land values facing parks and water bodies often result in a concentration of taller buildings,” says Chris “This acts as a wall, hindering the dissipation of cooler air deeper into the urban environment. The solution lies in having a mix of building heights and permeability in the streetscape.”

Cities are already taking action by appointing heat officers, redesigning public realms, greening urban areas and promoting energy-efficient building codes that consider not only winter lows but summer highs. There’s more to do, and heat itself is one part of a larger puzzle: excessive heat exacerbates air pollution, brings greater risk of wildfire, and heightens the risk of flooding too.

Extreme heat, unmanaged, undermines the attractiveness of a city – not just as a place to live, work and play, but as a place for investment and business expansion. With global temperatures set to exceed the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit on pre-industrial levels in the coming years, the pressures facing cities, and the real estate within them, are only growing.

Explore the latest articles in our Four Elements Series – Air, Earth, Fire and Water