Healthier, more inclusive, more environmentally focused. A sustainable city must be all of these things. It needs to develop its economy while keeping social and environmental impacts in mind.

More than half the world’s population live in cities – a number forecast to rise to almost 70% by 2050. That’s why UN Sustainable Development Goal 11 calls for cities to follow a path of more inclusive and sustainable urbanisation to combat the effects of rapid development.

Social challenges such as housing affordability intensify as population growth outpaces the construction of new homes, and resources such as water and air become more in demand and more polluted. Meanwhile, climate change means extreme heat is becoming more common – and urban areas are especially at risk.

The challenges facing cities are complex and multi-faceted, says Marylis Ramos, Director of Savills Earth Advisory Services: “Sustainability is a network of things – there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. A successful sustainable city needs to respond to its context, whether that’s climate hazards, social challenges or use of resources.”

Doughnut economics: changing the goal

Becoming truly sustainable may mean a reset in how cities measure success. The ‘doughnut economics’ model, for example, argues that measuring success by GDP growth alone is short-sighted. It calls instead for all human needs to be met, but without overusing the Earth’s resources. In other words, cities must have one eye on the environmental and social impact of their economic growth.

That means when we’re planning and managing our cities we need to put a greater emphasis on the environment, people and travel. One concept that’s come to prominence is the idea of 15-minute cities, where most daily needs can be met within a 15-minute journey by walking, cycling or public transport. This template for well-connected, mixed use, hybrid communities that promote wellbeing has its roots in history. Many of the world’s leading cities have evolved out of a series of linked communities; London is a metropolis formed from intertwined villages, for example.

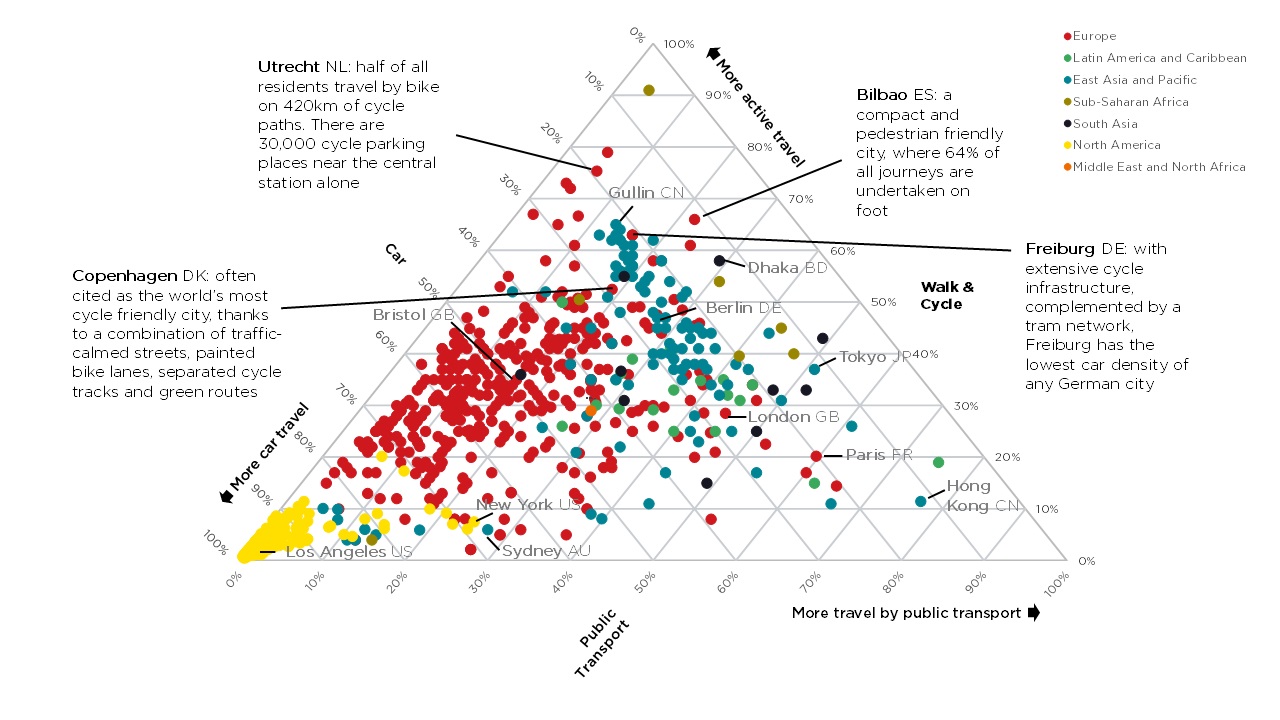

Mobility is central to a sustainable city’s success. Urban travel accounts for 40% of passenger transport’s global carbon dioxide emissions and contributes significantly to city air pollution, so greener solutions are imperative. The graphic below shows how city dwellers in different regions travel. It’s clear from this how North American cities are geared to cars, whereas Asian cities are much more reliant on public transport and walking. The graphic also illustrates how a few standout cities in Europe, such as Copenhagen in Denmark and Utrecht in the Netherlands, are improving their sustainable travel networks.

Travel modes by city

Source: Savills Research using Cities Moving

Sustainable cities are attractive to investors and occupiers

From an investment point of view, assets in sustainable cities may be less susceptible to the impacts of extreme weather or social shifts, resulting in lower insurance costs and greater long-term stability. A more complete assessment of a building’s environmental impact – such as including scope 2 and 3 emissions – also boosts a city’s sustainability credentials, further enhancing its appeal to investors.

Sustainable cities make sense for occupiers too, if they want to attract and retain the best and brightest talent. A globally mobile workforce increasingly favours urban areas that prioritise sustainability and inclusivity, enhancing quality of life. That’s particularly the case for highly skilled, younger people, who have been shown to prioritise these factors in their relocation decisions.

Leading sustainable cities

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all model for a sustainable city. It’s about each area addressing its unique challenges. These five cities have excelled by reacting to their specific circumstances.

Singapore

Despite being a land-constrained city-state home to 5.6 million people, this self-styled ‘City in a Garden’ has kept about 50% of its land as green space. This has helped protect the biodiversity of once-rare species and prevent flooding.

Although population density has threatened to jeopardise housing affordability, the Singapore Government has addressed this through its vast public housing programme. More than three-quarters of the population live in properties built and sold by the Housing & Development Board and 90% of citizens own their own homes. More broadly, the city’s Green Plan aims to see 30% of Singapore’s food produced locally.

Davao City, Philippines

Davao City is one of the least-polluted cities in the Philippines, thanks to the ALI Davao Carbon Forest project. It has planted over 30,000 native trees in the Davao City suburbs, creating a new green space and improving the city’s air quality.

It is also no stranger to extreme climate events. The city has suffered monsoons, earthquakes, flooding and landslides. In response, it has emphasised a community-based approach involving regular drills and seminars to educate the public. In addition, the government has focused on improving drainage infrastructure and riverbank protection to protect low-lying areas from flooding.

Vancouver, Canada

In 2023, emissions from wildfires across Western Canada quadrupled the country’s annual emissions and temporarily made Vancouver one of the most polluted cities in the world. To combat this – and protect vulnerable populations – the city introduced cleaner-air spaces, with high levels of filtration, in community centres and libraries.

Through its ‘Greenest City Action Plan’, which was completed in 2020, Vancouver created more green jobs, implemented the greenest building codes in North America and invested in sustainable transport. Renewables already account for more than 95% of the city’s energy and it aims to be zero waste by 2040, through effective recycling and composting programmes. Over the past 15 years, waste going to landfill has dropped by 36%.

Freetown, Sierra Leone

Located near the equator, Freetown has very little respite from urban heat – which will only get worse as the climate crisis intensifies. Rapid population growth has led to less vegetation and more heat-intensifying surfaces, especially around the informal settlements that house more than a third of the city’s population.

In 2021, Freetown – a founding member of City Champions for Heat Action alongside Miami and Athens – introduced Africa’s first Chief Heat Officer. This led to the application of heat-reflective roofing sheets made from recycled plastics to roofs in informal settlements. Initial results showed falls in temperatures of as much as 6°C.

Bergen, Norway

Ranking top for ESG in the Savills Resilient Cities Index, Bergen has shown leadership in several aspects of sustainability. Hydropower, which pushed Norway to the forefront of global renewable energy production, now produces more of the country’s energy than any other source. Bergen’s port is home to a 100% renewable shore power facility – it is Europe’s largest – which dramatically reduces pollution from docked cruise ships.

Sustainable transport continues in the compact and walkable city centre, where most newly-purchased cars are EVs. Norway also fares well in social inclusion; expenditure supporting disadvantaged and vulnerable groups is much higher than the EU average.